Minnesota Needs More Pathways Into the Classroom, But Concerns with PELSB Process Persist

By Krista Kaput

In 2017, Minnesota changed state laws to allow alternative teacher preparation programs to operate outside of higher education. We’ve been closely tracking how this law is being implemented through the Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board (PELSB), and last week, we testified with significant concerns about the program approval process.

Transforming Minnesota’s teacher preparation programs so they address the needs of students must go beyond lip service. Gatekeepers are stubbornly holding onto tradition and the ways Minnesota has always done things—all of which resulted in the problems we face today. Instead, we need to think of new ways to recruit, retain, and train educators, and that starts with rethinking our teacher preparation programs.

The Need for Change

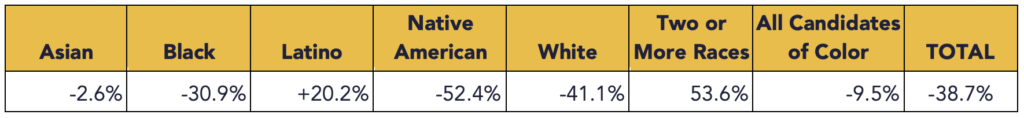

Over the past decade, Minnesota has seen a drop in the number of people pursuing teaching careers—including for teacher candidates of color, which is a significant problem when the state has been actively investing millions to try and increase the racial diversity of the teacher workforce. Only 4% of Minnesota teachers are people of color, and that number has barely moved for years.

The state has to make significant changes to curb shortages and attract more people to the profession, including adapting our training models to meet the needs of today’s workforce. Alternative teacher preparation is a critical part of this, both to better serve nontraditional candidates and to improve teacher diversity, where many alternative programs have demonstrated success and explicit missions.

Change in Minnesota Teacher Prep Enrollment by Race, 2009-2017

Source: Higher Education Act Title II Enrollment Data Reports

Strong Programs Face Substantial Barriers

It’s critical that as Minnesota launches new innovative teacher preparation models, we uphold quality and standards without creating undue barriers that do nothing to support student success.

Unfortunately, we’re seeing the pendulum swing into troubling territory. Based on close tracking of the approval process, as well as the relevant laws and regulations, we flagged several barriers:

- Subjective and inconsistent reviews of alternative teacher preparation programs. The lack of a formalized and objective application process has led to inconsistency in review and gives PELSB staff significant discretion over the interpretation of submissions. One specific concern is that during the review process, applicants have different reviewers on one round than they do in the next, resulting in inconsistent feedback on whether and why a program application meets standards.

- Biased and conflicting guidance from agency staff. We understand that PELSB staff don’t have all the answers—they’re human. However, when their interpretations and requests are not accurate or aligned to statute, the stakes are very high. Applicants have reported receiving instructions that are loose interpretations of policy and that cite the incorrect statute and/or rule. This has led to applicants bending over backward to satisfy staff requests, doing extra work to meet arbitrary requirements that aren’t related to improving their programs or teacher outcomes.

- Tradition standing in the way of change. Most of the independent program reviewers—those who determine whether to recommend a teacher preparation program for approval—are part of established institutions of higher education. In some cases, their knowledge of teacher prep norms is an asset, but in other cases, it blocks the new thinking and explicit efforts to advance new delivery models. Some reviewers have exhibited bias against alternative teacher preparation programs, calling them “the competition” or asserting that they don’t think an alternative preparation program could run without an institution of higher education. This stands in the way of innovation: as Albert Einstein said, “we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

- Disregard for the law. The 2017 alternative teacher preparation statute (122A.2451) requires an alternative teacher preparation program be approved if they meet six specific requirements, naming that outside of these, they are permitted to use nontraditional criteria related to qualifications of teacher educators, program delivery, and more. Nonetheless, there remains a significant sense of fear related to these new, innovative, and nontraditional methods. Instead of following the law, which was created to inspire a new way of thinking about teacher preparation, the board, staff, and many of the reviewers continue to revert to the old ways of thinking—like insisting on teacher educators having an “advanced academic preparation” (like a Ph.D.) when statute explicitly states that nontraditional criteria, like being an effective classroom teacher, can be used instead.

- Misalignment of unit and program regulations. The current regulations defining the unit and program approval process were made when Minnesota only had teacher preparation programs that were part of institutions of higher education. The language is tailored to this assumption. The regulations are currently being redone, but in the meantime, programs are at risk of being denied based on a process explicitly designed around the old model.

Alternative teacher preparation programs are a proven way to increase teacher diversity, fill shortage areas—particularly in special education and career and technical education—and introduce experienced professionals to the teaching profession. Considering that Minnesota has teacher shortages and too few educators of color, it’s imperative that PELSB have a fair and objective process for approving teacher preparation programs that don’t perpetuate the status quo.