Proposed Changes to MN Special Education Law Erode Protections for Students

By Matt Shaver

In case you missed it, a last-minute bill was introduced in the House Education Finance Committee that would bring about a drastic change in the way that special education works in Minnesota— unfortunately, not for the better. A provision of HF 2357, which was wrapped into the omnibus bill that just passed in the House, undermines a fundamental principle of Minnesota law, eroding protections for students with disabilities that were codified more than 60 years ago.

A Brief History of Special Education Law in Minnesota

The 1950s Minnesota Legislature was not all that different from the Legislature of today. The rural/urban divide, party politics, and differing views on the dynamics of local control and the role of state government influenced the direction of legislation much like it does in 2021.

At the direction of Governor Orville L. Freeman and the insistence of dedicated parent advocates, an interim legislative commission formed in 1955 to study what education was like for kids with disabilities in Minnesota, search for national best practices, and make policy recommendations.

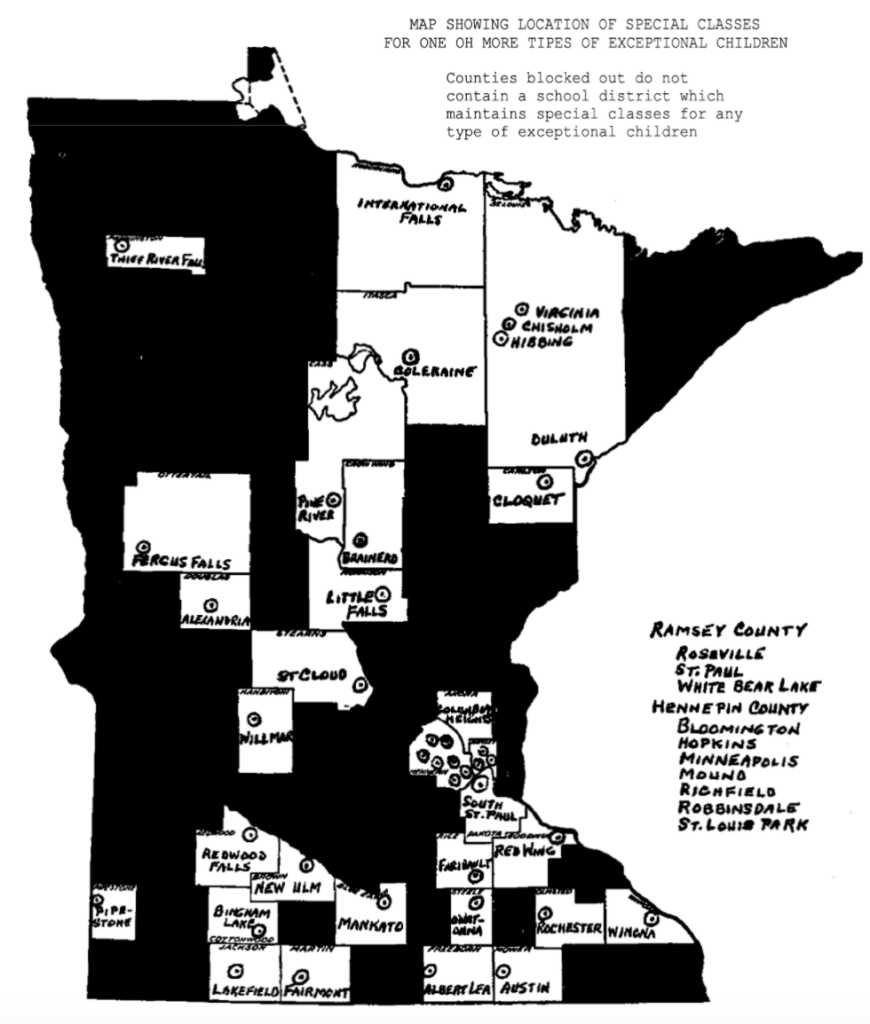

Minnesota provided special education courses beginning 1915, but since it was not mandated, forty years later only 30 out of 87 counties had special education programming. Many children with disabilities either had no school to go to, or they were segregated and institutionalized—sent to learn far away from home because their resident districts did not have programming.

The Legislature passed a groundbreaking policy in 1957 to address this, requiring special education in Minnesota schools. (This was nearly twenty years before the right to a Free and Appropriate Public Education [FAPE] for all students with disabilities was guaranteed federally by the Education for All Handicapped Children Act—now known as Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [IDEA].) By requiring every district to provide special education services, or allowing a student to enroll somewhere else at the resident district’s expense, the Minnesota Legislature guaranteed an education to all students near their home and told children with the highest needs: You deserve an education no matter where you live and no matter your need.

Districts Pushed Back Then, and They Are Now

One provision in the Minnesota law was and still remains a sticking point for a few districts today. It is the responsibility of the resident district (where the child lives) to provide for special education services—which includes funding—even if that student attends school in another district. The goal here was serving students and not allowing schools to pass the buck: even if you can’t meet a student’s needs, you must still pay for their services elsewhere.

Originally this cut differently for larger school districts that already had special education programming: Minneapolis Public Schools was resistant to these changes, because it meant that students who didn’t live in Minneapolis would now have a special education option in their own community creating the potential for losing out on funding for MPS. Today, the big debate still focuses on district funding, but from the opposite side of the coin: what happens when special education students seek programming outside of their home district?

Proposed Changes to Special Education Funding

Despite committing to special education students in principle, both the state and federal government have consistently fallen short on their end of the bargain, never meeting their funding obligation to support essential services. There’s a real and meaningful gap that the House bill tries to address with a gradual funding increase.

Unfortunately, the bill doesn’t stop there. It also seeks to reduce costs for districts by capping how much they must reimburse for students who attend charter schools. This is a big shift from the current model, where cost-sharing helps ensure prudent decision-making. Instead, districts just won’t be on the hook when students with intensive special needs enroll in a charter. Without additional funding, this could effectively drive a race to the bottom, where ultimately, no one is on the hook to ensure an effective education for students with special needs—triggering exactly the problem the law sought to avoid by creating an incentive to underserve students with the greatest needs. More important than district or charter school bottom lines are the impact to students: loss of services, changes to class sizes, and more unearned, unnecessary hardship.

By undermining a fundamental principle of Minnesota special education law 125A.03, this would erode protections for students with disabilities that were codified more than 60 years ago.

By undermining a fundamental principle of Minnesota special education law 125A.03, this would erode protections for students with disabilities that were codified more than 60 years ago.

Proponents of these changes will likely argue pejoratively that charter schools are giving students with disabilities “cadillac services”—somehow being frivolous in developing effective services for any student that needs them. Giving students with disabilities the services they need and creating an “appropriately ambitious program” is something that I would hope every educator and every school is striving toward. Special education is expensive—but we are nowhere close to overspending on student needs, and need to stay focused on the core problem of underfunding.

Another common complaint is that it is unfair that schools have to pay for services for students who do not attend their district when they do not have input on what services that student receives. However, oftentimes a student with a disability will enroll in a charter school with an IEP written by their home district, so the charter school follows that plan and the home district pays for the services.

All of this applies not just to charter schools, but to neighboring districts as well. Whether a Minneapolis student enrolls in Edina, Robbinsdale, or a local charter, MPS is still responsible for the cost—and vice versa: they are reimbursed millions of dollars a year for making service decisions for students from other districts that open-enroll. Rates across districts vary quite a bit too: for example, as of 2016, Duluth spent about $15,500 per special-education student, and Hibbing less than $11,000. It’s curious that they are not proposing to change that arrangement, isn’t it?

These changes do not solve the challenges of special education funding. Instead, they seek savings for districts by placing arbitrary caps that are fundamentally unproductive—leaving the underlying problem unaddressed while doing harm to our students with the greatest needs.

We can do better; our kids deserve better.