What’s Working Best to Recruit and Retain Teachers of Color in MN

By Daniel Sellers

The new 2019 Minnesota Teacher Supply and Demand report shines a light on Minnesota’s dire shortage of teachers of color, and how well district strategies to curb it are (or are not) working. Given the mounting research on the benefits of teacher diversity, state leaders need to get serious about tackling the problem. Thankfully, the new report points to a few promising ideas—while also reminding us that we need a lot more ideas, too.

FIRST: TEACHER DIVERSITY MATTERS

When students of color have teachers of color, they’re more likely to be placed in gifted programs and less likely to experience disciplinary referrals. They also feel more cared for and interested in their homework, and are ultimately more likely to graduate.

And, yet, in Minnesota, just 4 percent of licensed teachers are teachers of color or American Indian. What’s worse, this number hasn’t budged in recent years, even as the student population grows more diverse; in 2017-18, 34 percent of Minnesota students were students of color. Sadly, many of them may never have a teacher of color: A whopping 38 percent of Minnesota school districts have zero teachers of color or indigenous teachers.

SO, HOW ARE EFFORTS TO INCREASE TEACHER DIVERSITY GOING?

Recruitment

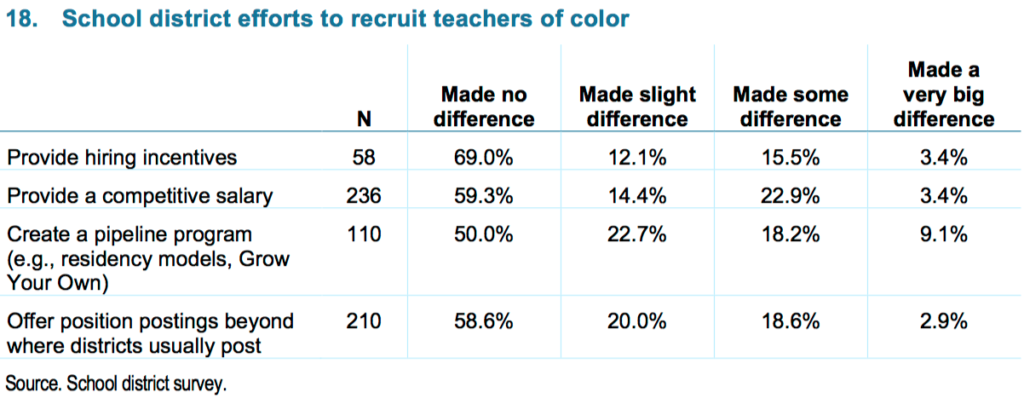

According to the new supply and demand report, more than 90 percent of Minnesota school districts report difficulty recruiting American Indian, Asian, Black, Hispanic, and other teachers of color. It’s no wonder that many are trying a variety of approaches to recruit more diverse educators, including hiring and salary incentives and adjusted hiring timelines. But, in the districts that have them, home-grown teacher pipeline programs, from Grow Your Own to residency models, are making the biggest difference.

Licensure

The report also shares that 14 percent of teachers of color work under “special permissions” or “variances,” compared to 4 percent of white educators. Moving forward, under Minnesota’s new tiered teacher licensure system, the vast majority of these teachers will be given Tier 1 and Tier 2 licenses, which were designed to take the place of special permissions and variances. Recently, the Professional Educator Licensure and Standards Board reported to the Legislature that 9 percent of teachers with Tier 1 and Tier 2 licenses are American Indian or teachers of color (compared to just 4 percent of all licensed educators).

A whopping 38 percent of Minnesota school districts have zero teachers of color or indigenous teachers.

Taken together, these data points suggest that schools are having better luck hiring teachers of color with the unique backgrounds and skills to fill specific positions. Those educators just haven’t always completed traditional teacher training for the courses they’re teaching; instead, they may have taught in similar fields, gained invaluable classroom experience in support staff roles, or worked hands-on in unique content areas. It turns out that when we grant licensure to these qualified individuals—whom school districts clearly want and need—our teaching force grows more diverse.

Retention

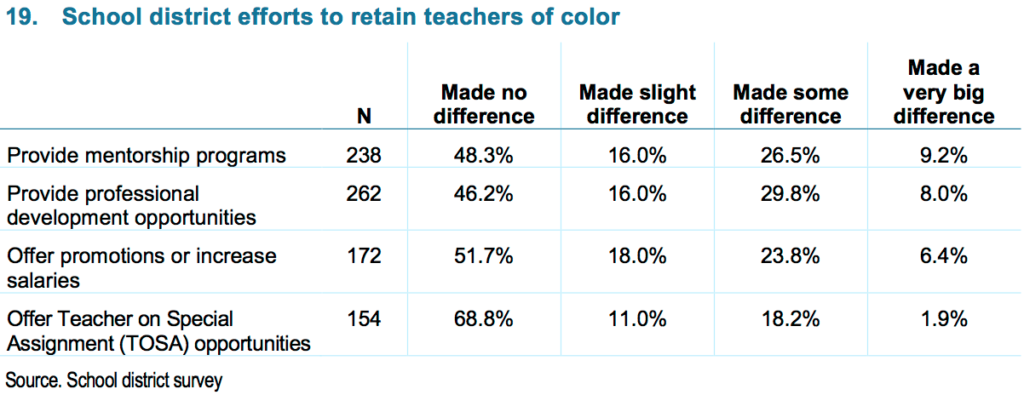

Finally, we know anecdotally that teachers of color face barriers not only into the classroom, but also once they get there. When it comes to retaining teachers of color, school districts report that providing mentorship programs and professional development opportunities make a bigger difference than increasing salaries or offering promotions. Another way to remove barriers is to ensure that educators on special permissions and in Tier 1 and Tier 2 have a clear path to a permanent Tier 3 license.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

To increase teacher diversity, state leaders need to bring more urgency and creativity to an issue that has not budged for too long. They should start by looking at what’s working best today across Minnesota school districts: alternative teacher preparation models, varied and straightforward pathways to licensure, and ongoing opportunities for professional growth and support.

It’s also critical that policymakers and school leaders listen to teachers of color themselves. For example, if PELSB and state leaders move forward with a statewide survey to better understand teacher attrition, they must—as Minneapolis Public Schools did recently—research the specific reasons why educators of color leave the classroom.

There’s no doubt that Minnesota has a problem with teacher diversity. But it’s also clear that we have many tools and insights to help us fix it. We just need the will to make it happen.